Is Diffusion the Future of LLMs?

LLMs feel stuck while image models leap forward. Why? It's not just about data—it's about how they generate. From Will Smith's spaghetti to the future of AI

TL;DR

Computer vision models progress with dramatic, visible leaps, while LLMs feel static and slow by comparison.

LLMs scale via brute-force but face a looming shortage of high-quality text data.

Vision models achieve more with fewer parameters and greater architectural variety.

Diffusion models offer key advantages (bidirectional context, error correction, and parallelism) but adapting them to text remains technically hard.

Despite challenges, diffusion remains the leading hope for breaking through LLM limitations.

The Visibility Gap

It was less than three years ago that ChatGPT was released, yet it already feels like ages. In a matter of months, the entire ecosystem was reshaped, with companies no one had heard of suddenly toppling fragile giants we once thought immovable. For the first time, the gap between theory and application had never been so thin, making mathematicians and researchers more relevant, and more desirable, than ever.

Concurrently with the LLM wave, computer vision became generative as well. The first big names (DALL·E, MidJourney, and Stable Diffusion) took the internet by storm, giving mainstream audiences the ability to generate images from prompts for the very first time. The limitations were obvious: the infamous six-fingered hands, the lack of consistency across outputs, and other uncanny artifacts. All these shortcomings were on full display in one of the most iconic, hilarious, and uncanny early examples of generative video: Will Smith eating spaghetti (2023).

A lot of articles were written about this. Many, including brilliant minds, argued that these flaws were essentially impossible to fix, and to be fair, their reasoning was solid. Yet it now feels like those issues weren’t obstacles at all. Within a year, we were already watching an AI-generated Will Smith eating spaghetti like a champion (funny enough, the real Will Smith has since embraced the uncanny in his own way, using AI to add crowds to his concerts in officially published videos).

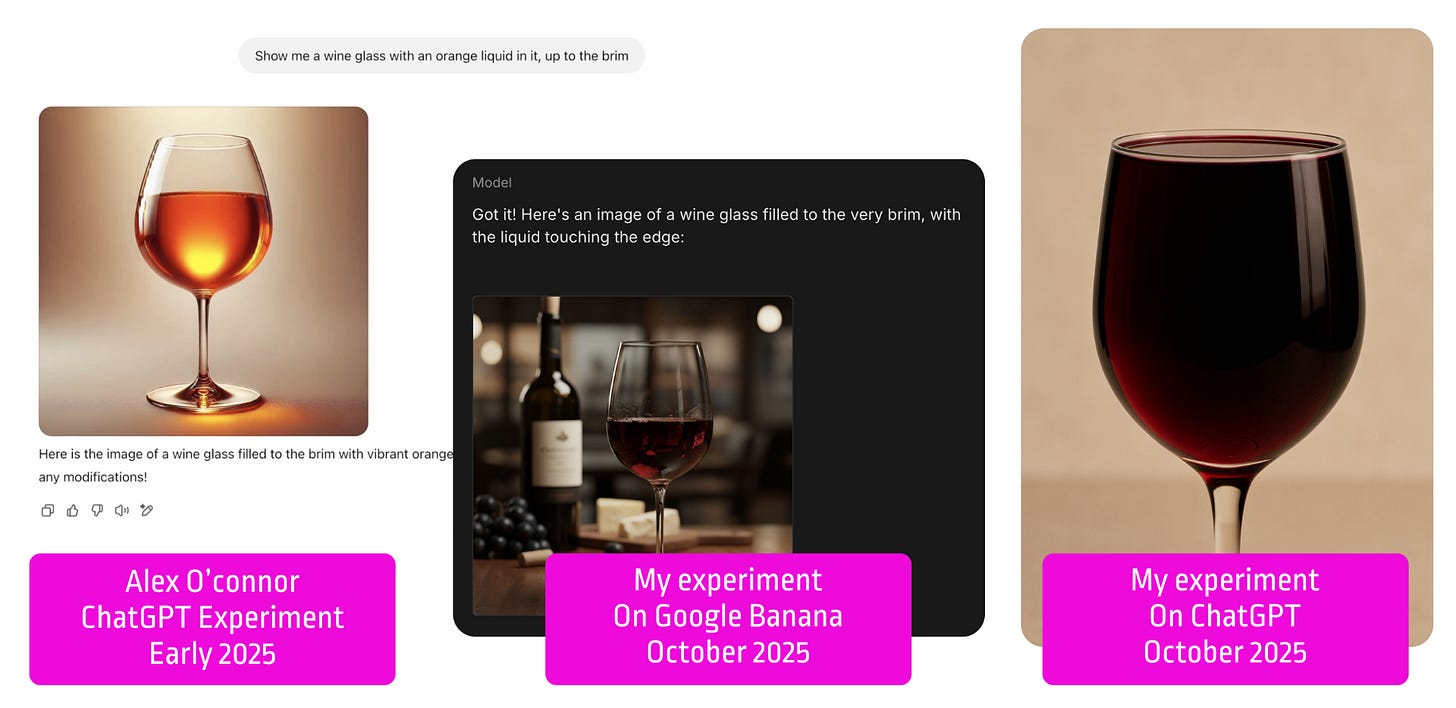

I also remember watching a video from Alex O’Connor where he asked ChatGPT to generate a glass full of wine.

Despite numerous attempts with different strategies, the model consistently failed. The explanation was straightforward: it had been trained on massive datasets of labeled images, but glasses filled all the way to the brim are rare in real-world data, so the model had hardly ever “seen” them. Another strong argument.

Seven months later, I decided to try it myself with a surprising result. Nano Banana, the fresh new image generation/editing feature within Gemini, fails miserably. But ChatGPT nailed the glass-full-of-wine test in a single attempt. OpenAI’s team probably expanded the dataset with synthetic data. But once again, it showed that “impossible” was never really impossible. And it reinforced the feeling that computer vision is leapfrogging at a pace that makes LLM progress look almost static.

So why the gap? Each new iteration of LLMs seems to need a wave of marketing claims and flimsy benchmarks to prove they are improving. Generative computer vision, on the other hand, makes giant, undeniable leaps, astonishing both mainstream audiences and experts with nothing more than a single prompt.

Vision Models, in Three Flavors

Vision models are a large family with many categories and not-so-compelling names, so it’s easy to get confused. We’ll classify them into three main groups:

Discriminative Computer Vision Models. The old school. They describe what they see. Example: This is a hot dog 🌭

Vision-Language Models (VLM). Trained on paired image + text. They usually perform worse than specialized models in isolation, but outperform when the task requires combining both, like interpreting charts.

Generative Computer Vision Models. I’ll mostly focus on those, since they are the most prominent, the most impressive, and the ones most people mean when they talk about computer vision.

Smaller, Cheaper, Stronger 🎶

At first glance, it seems intuitive that images, with more information and complexity than text, would require bigger models with far more parameters. Interestingly, the opposite is true. For perspective, even today’s Stable Diffusion 3 has “only” 800 million to 8 billion parameters. In the LLM world, that would be categorized as fairly small, closer to the “SLM” (as in small language model) family.

Computer vision models operate under fundamentally different computational characteristics. Vision transformer linear layers often achieve an order of magnitude higher efficiency than text, sometimes reaching 100–200 FLOPs per byte at scale, while LLM attention operations typically reach only 0.5–10 FLOPs per byte during inference. This represents roughly a 10–100x efficiency advantage for vision models in arithmetic intensity, the ratio of computational operations to memory operations. LLM inference remains fundamentally memory-bound, with studies showing that “over 50% of the attention kernel cycles stalled due to data access delays for all tested models.” In contrast, vision models’ “parallel matrix operations are well aligned with GPU architecture, allowing them to fully exploit the large number of available cores and memory bandwidth.”

Vision models also exhibit substantially more architectural diversity than language models, ranging from Vision Transformers scaled to 22 billion parameters, to lightweight architectures like YOLO, hybrid CNN-ViT approaches, and specialized 3D vision architectures. This diversity enables more scalable and versatile systems, optimized for specific hardware constraints.

In short, vision models achieve superior hardware utilization through higher arithmetic intensity and benefit from greater architectural diversity. This explains the rapid progress in computer vision compared to the scaling challenges faced by language models, as vision architectures are fundamentally better suited to exploit modern GPU hardware capabilities.

Scaling Issues and Fossils

Meanwhile, LLMs can’t stop growing, to the point that there is nothing left to ingest, or at least nothing of sufficient quality.

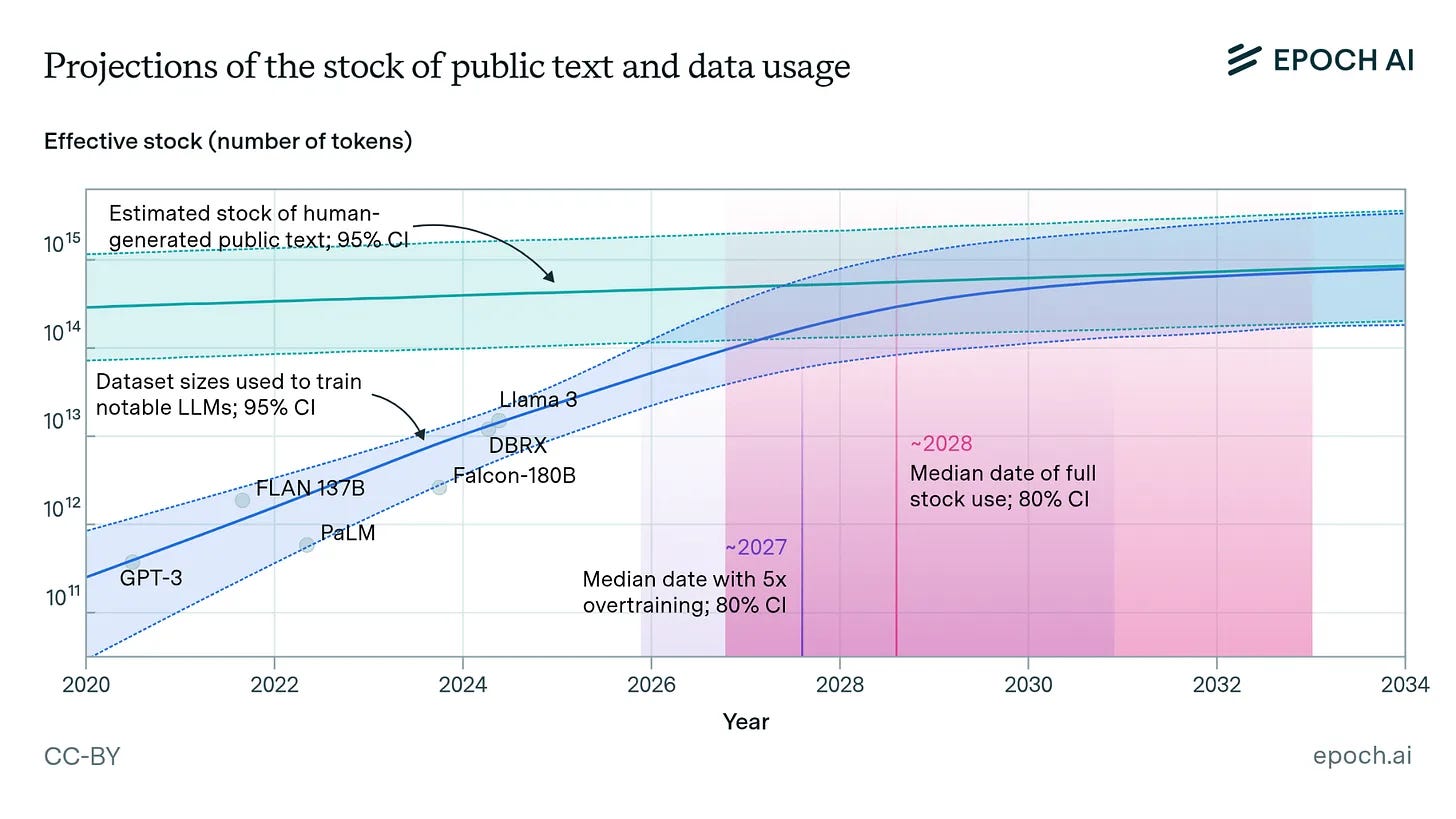

Most state-of-the-art LLMs today are trained with hundreds of billions of parameters, and some claim scales in the trillion range. The major caveat is that simply increasing parameter count or training volume yields diminishing returns: model quality improves more slowly, and extracting additional value from ever-larger corpora is increasingly marginal. Worse, research converges on a shortage of high-quality text, calling this finite resource “the fossil of AI.” Even optimistic estimates project we’ll run dry between 2026 and 2032. The literature is abundant about this limit, and the dangerous reliance on synthetic (or partly synthetic) data to fill in the gaps.

Best case: improvements plateau.

Worst case: performance degrades with poor synthetic data.

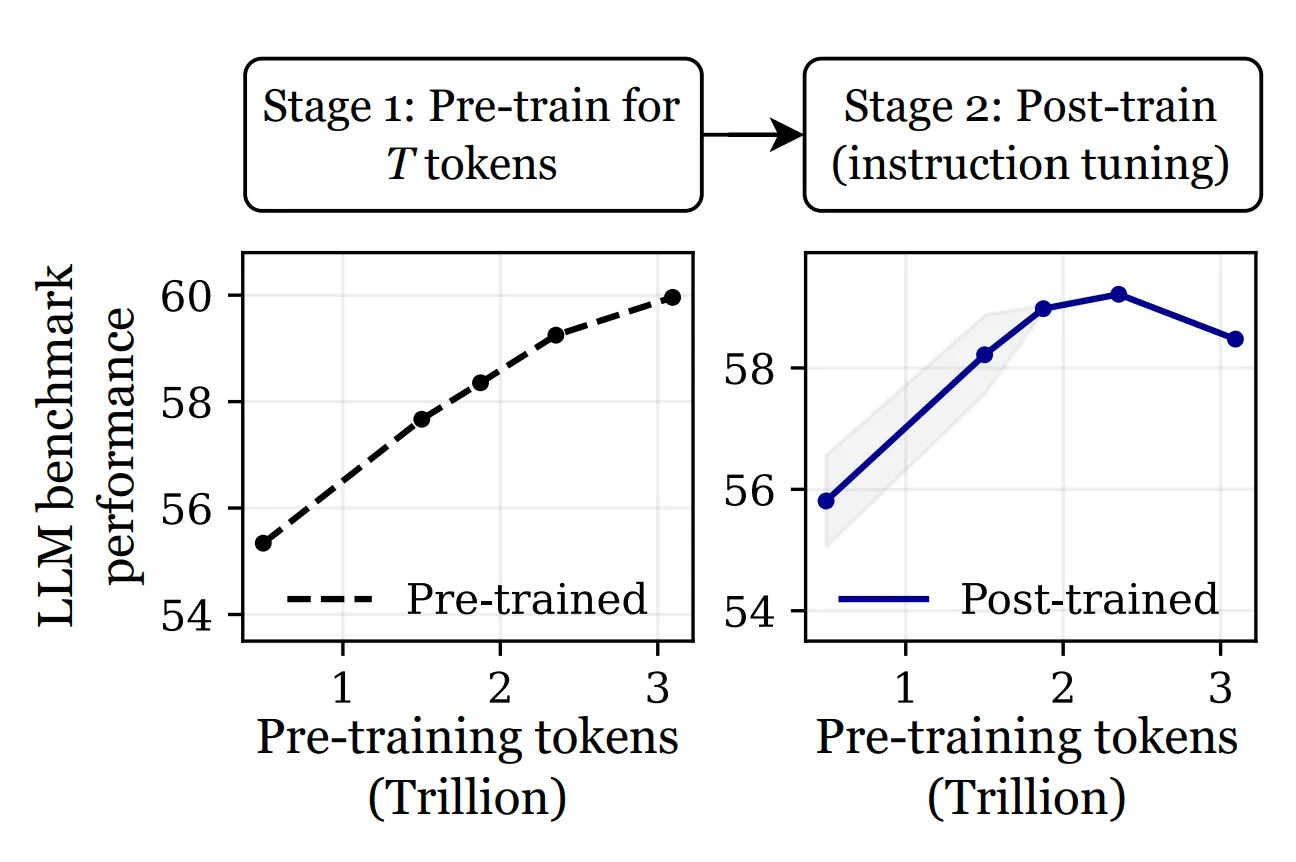

“Overtrained Language Models Are Harder to Fine-Tune“ argues that uncontrolled large-scale training on more data can actually lead to worse performance after fine-tuning. For example, OLMo-1B trained on 3 trillion tokens performed over 2% worse on standard benchmarks compared to its 2.3 trillion-token counterpart. The more you train, the harder it becomes to adapt the model to new tasks, especially when the data is of low quality.

What makes this situation worse, is that LLMs have mostly converged on one winning formula (the transformer) and are essentially variations on the same theme, brute-forcing their way to predicting the next token. It’s as if the industry agreed on one recipe, and now everyone is just arguing about the seasoning.

Even if there is still room for improvement, such as this recent paper “Reinforcement Learning on Pre-Training Data“ which suggests that significant progress can be achieved through pre-training data selection without human supervision, it’s hard to expect a major leap within the pure autoregressive paradigm.

The Diffusion Advantage

Among the many methods for generating images, diffusion dominates (even if the boundaries are thin and models are often hybrids of several approaches, such as Gemini 2.5 Flash Image, which may benefit from a transformer–diffusion architecture). Instead of left-to-right token prediction, as in LLMs, diffusion models start with noise and iteratively refine the entire output simultaneously through a series of steps.

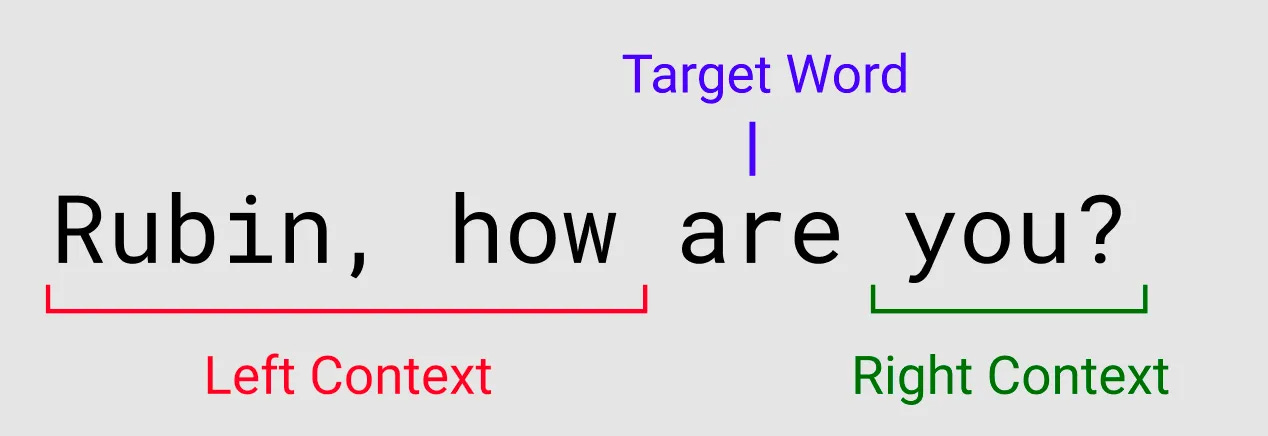

This iterative refinement process provides many key advantages over the current autoregressive paradigm. Bidirectional context modeling allows diffusion models to incorporate information from the entire sequence during generation, unlike autoregressive models that can only condition on previous tokens due to causal masking. This bidirectional attention is crucial for encoding global context, especially in long and complex sequences.

Error correction is perhaps the most intuitive advantage. Unlike autoregressive models, where early mistakes propagate irreversibly through the entire sequence, diffusion models can revise and correct errors at each denoising step. For instance, a wrongly spelled name can be fixed (or at least normalized) as the content is refined.

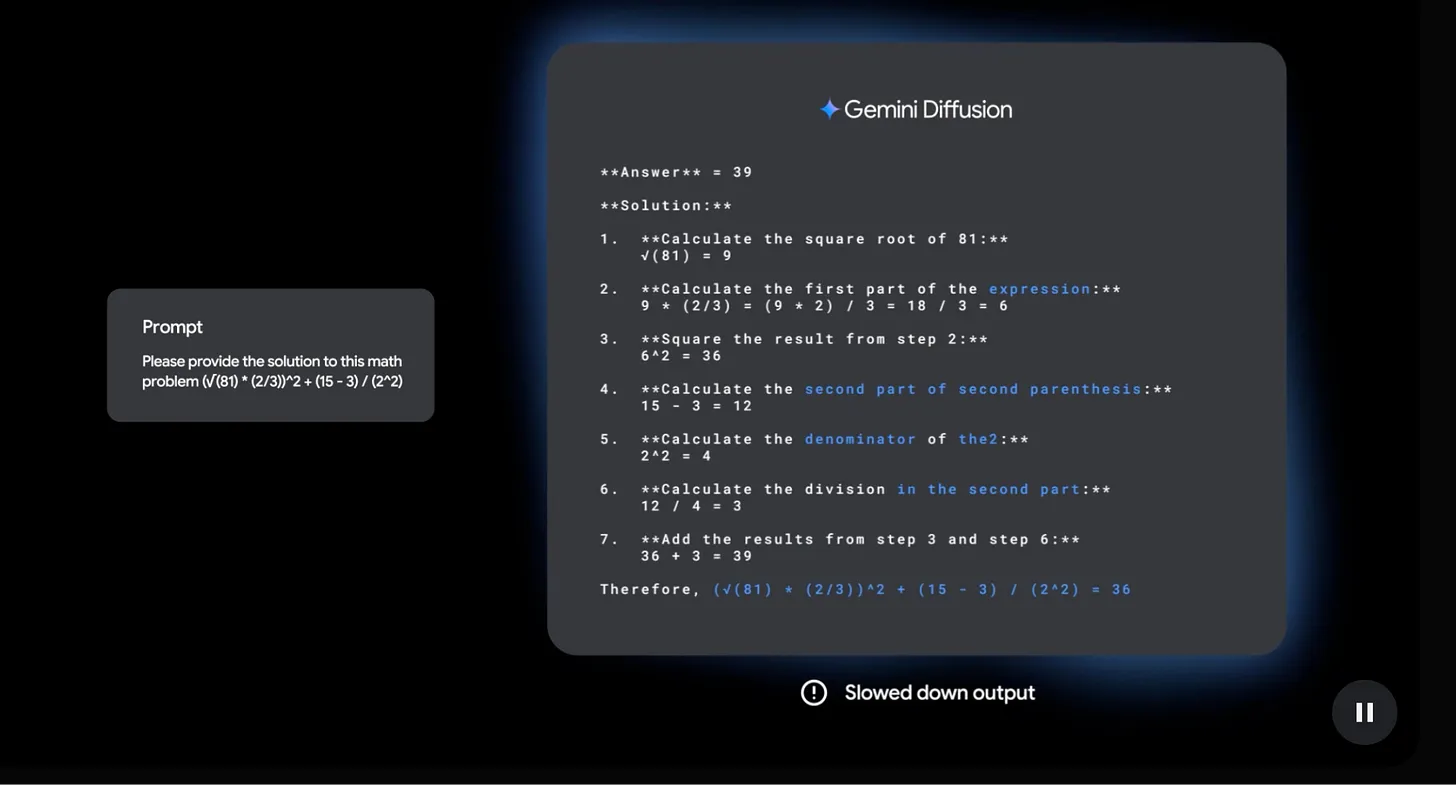

Parallel generation enables diffusion models to produce multiple tokens simultaneously rather than sequentially, though this requires multiple denoising steps, as with images. Google’s Gemini Diffusion model exemplifies these advantages, claiming 1,000–2,000 tokens per second (~10x faster than standard Gemini models) while maintaining superior accuracy on tasks requiring global coherence, even though it is still experimental in areas such as complex reasoning and multilingual capabilities. This approach also provides enhanced controllability, since users can fine-tune generation attributes at each denoising step and trade speed for quality by adjusting the number of refinement iterations.

And perhaps most importantly, diffusion models can address challenging tasks like the reversal curse, where models must reverse learned associations. For example, if trained on “Colette is Kevin’s adorable dog,” autoregressive models typically fail when the question is reversed: “Who is Kevin’s adorable dog?“ Current LLMs can’t reliably identify “Colette“ as more likely than any random name. Research shows diffusion language models reportedly outperform AR models on specific reversal tasks, even if broader generalization needs more validation.

Not So Easy, Tho

How come Diffusion models aren’t used massively on text, then? Because all of this is mostly experimental, speculative and/or theoretical. Adapting diffusion models to text remains inherently difficult because language is fundamentally discrete (information that can only have specific, separate values, like counting the number of people in a room, you can not have half a person, or you can’t add noise to “dog” to get to “cat”) and highly structured, unlike images where diffusion operates smoothly over continuous pixel values. Applying noise to text data requires special techniques (such as token masking or random replacements) that often break linguistic coherence and make the denoising process unstable. The complex and long-range dependencies in language cannot be modeled with simple Gaussian noise as in vision.

Moreover, training diffusion models for text often demands many separate refinement steps (which, without proper optimization techniques like step distillation, can be much higher than the 20-50 steps typical in image generation), dramatically increasing inference cost. These technical obstacles, along with challenges in designing suitable loss functions (a way for the model to measure how wrong it was, so it knows how to improve next time) and effective noise schedules (the plan for how much “random corruption” to add step by step) for discrete data, have made it far more expensive and less straightforward to match diffusion’s success in vision within language modeling.

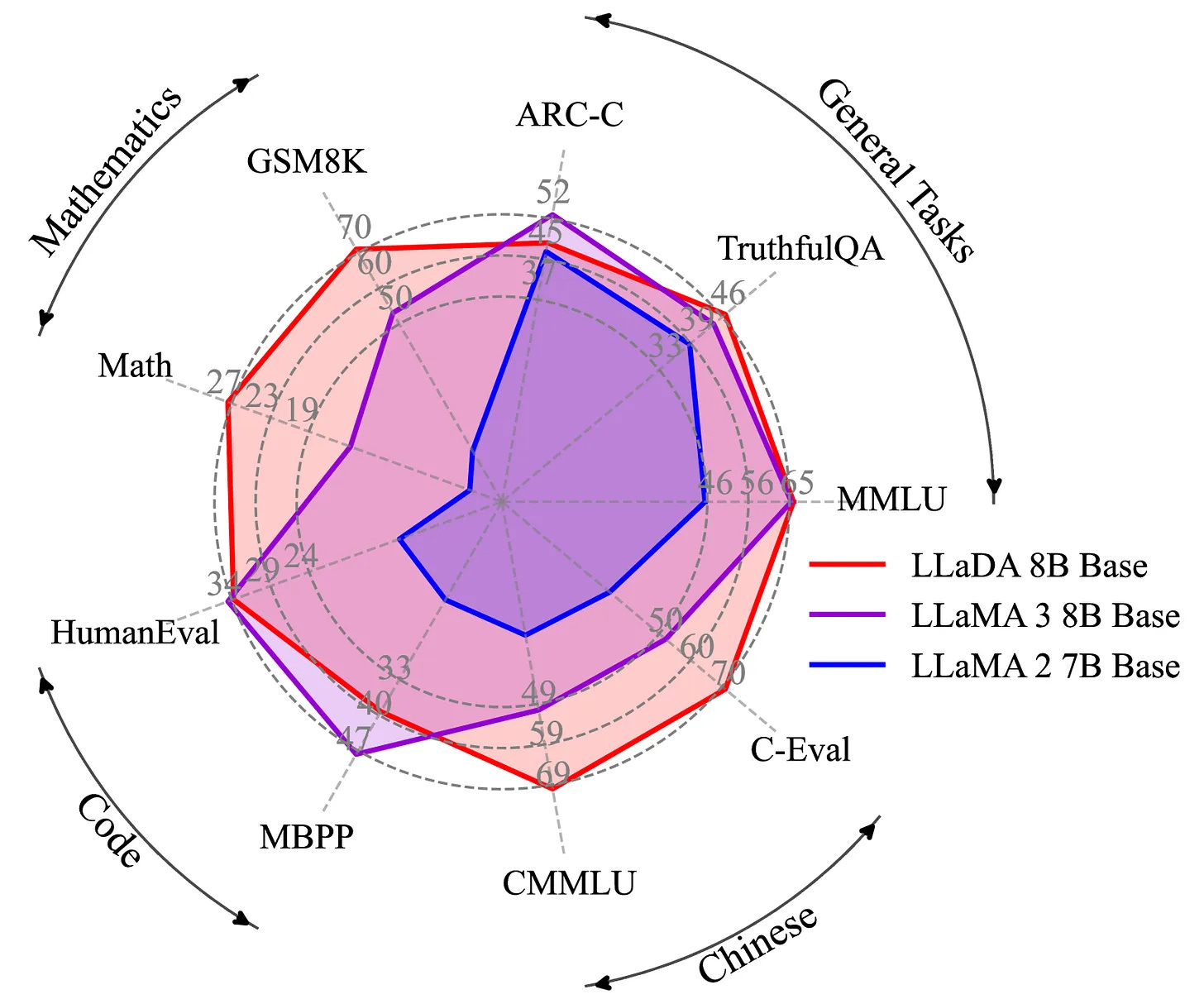

To give a reference (as of today, since things move fast), LLaDa 8B outperforms LLaMA 2 and is comparable to LLaMA 3 8B, but it required an engineering marvel to stabilize, and the architecture has not yet been demonstrated at 100B+ and would require significant additional research and resources.

The Path Forward

Despite all the obstacles ahead, a diffusion-based language approach might prove to be one of the best options to combine with pure autoregressive LLMs. Early results suggest this hybrid paradigm could help LLMs break out of their scaling plateau by changing how they generate: not predicting tokens in sequence, but refining drafts. Recent research even shows diffusion models can benefit from repeated data for up to 100 epochs (complete passes through the dataset), while autoregressive models saturate after just four. As we approach the limits of internet-scale text data, this efficiency advantage becomes critical.

And after all, diffusion makes more sense since humans don’t write by predicting the next word. We draft, revise, and refine. Maybe it’s time our LLMs did the same.

🙏 Thanks to Gabriel Olympie and Emmanuel Benazera for the suggestions and review!

I looked into diffusion LLMs beginning of the year! Interesting to look at the progression of things.

Kudos :)